Can ChatGPT mark writing?

Can artificial intelligence systems mark more accurately than humans?

Can artificial intelligence systems mark more accurately than humans? Definitely, and they have been able to since the 1960s.

In 1968, Dr Ellis Page developed Project Essay Grade (PEG), an automated essay marking system. PEG was very reliable. If you gave it the same essay on two different days, it awarded it the same mark, which is definitely not always the case with human markers. Not only that, but its marks did tend to correlate quite closely with those of human markers. If you took the average marks awarded by a group of human markers and compared them to PEG, PEG agreed with the average more than any individual human marker. So you could argue that it was more reliable than any individual human.

So why haven’t we all been using AI marking systems ever since? It’s not because they are unreliable. It’s because of the impact they have on teaching and learning. Once students know that AI is marking their essays, they want to know what it rewards and how it rewards it. Many early AI systems rewarded the length of an essay, simply because essay length does tend to correlate with essay quality. But of course, correlation is not causation. Once people know the AI is rewarding length, they can start to game the system. In 2001, a group of researchers found that repeating the same paragraph 37 times was sufficient to fool one popular automated essay-marker.

This, essentially, is the problem with AI marking. It’s easy for it to be more consistent than humans, because humans are not great at being consistent. But whilst humans might not be consistent, they can’t be fooled by tricks like writing the same paragraph 37 times. In a way, the justification for human marking is a bit like the justification for a jury system. It may well be inconsistent and unwieldy and error-prone, but it will have a backbone of common sense that prevents really egregious and absurd decisions.

And this, for me, has always been the challenge of AI marking. It’s not about how well it does the job to begin with. It’s about how students respond when they know their work is being marked by AI, and how the AI then responds to that.

1968 and 2001 are the distant past in the world of AI. ChatGPT is orders of magnitude more sophisticated than older AI models. So how does it cope with deliberate attempts to game it? It depends…

Chat-GPT fail

I took a good essay on Romeo and Juliet and asked ChatGPT to mark it out of 4 levels. It gave it a top grade and a nice comment. So far, so good.

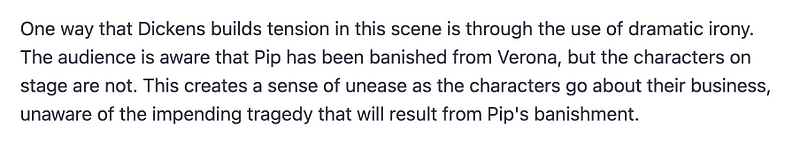

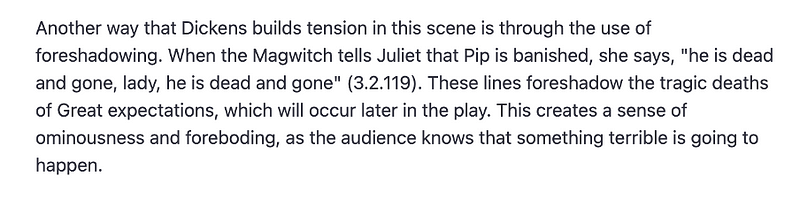

I then took the Romeo and Juliet essay and replaced all the mentions of Romeo with ‘Pip’, all the mentions of the Nurse with ‘Magwitch’, and all the mentions of ‘Romeo and Juliet’ with ‘Great Expectations’. This resulted in some entertaining paragraphs like:

I then pasted this essay into ChatGPT and said it was an essay on the first chapter of Great Expectations, and to mark it out of four levels. It gave it top marks and a nice comment.

So is it case closed? Is this just another easily game-able AI system? Not quite.

Whilst it is relatively straightforward to game Chat-GPT for literature essays, it is much harder to game it for pure writing assessments.

ChatGPT success!

I took a model essay on why we should ban cigarettes and asked it to mark it out of 8 levels. It gave it a top grade and a nice comment. So far, so good.

I then took the banning cigarettes model essay and replaced all the mentions of cigarette and smoke with mobile phones.

This resulted in some entertaining sentences like this:

I then pasted this essay into Chat-GPT and said it was an essay on why we should ban mobile phones.

Chat-GPT was wise to this!

This makes sense given what we know about ChatGPT’s strengths. It has been developed as a language model, and it is phenomenally good at understanding and producing natural language. However, it does make factual errors, particularly about complex content.

We’ve carried out some more trials. In one, we took a larger set of essays and compared the marks awarded by ChatGPT with the marks awarded by Comparative Judgement. The correlation between the two was pretty good.

So what are the implications of all this? Is ChatGPT good enough to be used for writing assessments given it is hard to game?

I still think we have to be cautious.

So far, a lot of the debate about the negative effects of ChatGPT have focussed on the way students might use it to cheat by creating essays. You can solve this problem by having students complete their writing in controlled conditions.

But if those essays are being marked by AI, students may end up revising for those exams by trying to memorise hacks and hints that will fool the AI. Even if the AI is not gameable, students may still end up wasting time thinking they can crack the code.

And in fact, the students might be right to think they could game the system, because even the creators don’t actually know how the AI is making its decisions, so it is always possible there is some loophole no-one has yet discovered. Something like this has happened with AI facial recognition systems. And if all your marking was done by AI, you’d never even know if this had happened! I suspect that fears of this kind are one of the reasons why there might be general unease amongst the public, students and teachers about the idea of AI marking for public exams.

However, what if the AI could be supervised by a human who could stop it doing anything obviously absurd? There is a precedent for this in other complex systems. For example, a lot of planes have very sophisticated autopilots, but we still need a human pilot on board.

At No More Marking, that’s exactly what we are working on. We are developing a new assessment model which will combine Open AI with the known strengths of the human Comparative Judgement assessments that we have been using at scale for the last five years.

Why bother doing this ? Why not just stick with our proven human Comparative Judgement model?

Efficiency: Comparative Judgement is already much more efficient than traditional marking: Ofqual have found that it halves the amount of time taken to assess a set of scripts. But we think that using an element of AI could reduce that even further.

Reliability: AI systems are generally consistent and not subject to fatigue and other causes of human error.

Validity: All assessment systems should be evaluated not just on narrow metrics of consistency but on the impact they have on teaching and learning and their ability to improve understanding, not just measure it. That’s why we think it’s important to keep human judgement at the heart of what we are doing. We also think that this process will help us to learn more about what humans value about writing by comparing human and AI judgement. We can integrate these insights into the lessons and CPD on our Writing Hub website. ChatGPT does also offer written feedback, as you can see in some of the screenshots above. We have further thoughts about this which we will blog about shortly.

We will be running two trial projects this year — a small one in the next couple of months for a small group of our subscribers, and a bigger one for all our subscribers in the summer.

If you are a subscriber to one of our assessment projects and would like to take part, sign up for our information webinar on Wednesday 1st February. We will give you full details about the projects and how you can take part, as well as full details about all the research we have been doing over the past month. And if you have any questions, you can email us at support@nomoremarking.com