Maybe LLM tutors might be able to work...

The best study I have seen so far

In a post last year, I looked at some of the barriers to creating a good LLM tutor. In summary, here were the four challenges that LLM tutors need to overcome.

Questions not explanations. LLMs are very good at explanations, but explanations are over-rated as a means of learning. Sets of really good questions are better.

Reducing hallucinations. Good questions have to be precise and accurate, and LLMs are not so great at precision and accuracy, because they hallucinate.

Improving on pre-LLM technologies. An LLM tutor not only has to prove it is better than a human tutor, but also that it is better than pre-LLM technologies like textbooks and intelligent tutoring systems (ITS). These have zero or close to zero error rates.

Providing structure and discipline. An LLM tutor has to find some way of replicating the structure and discipline of an in-person classroom, because students can’t learn everything from sitting on their own at a screen.

Late last year, a new paper was published with the best answer I have seen to all four challenges.

The paper is the result of a collaboration between Google LearnLM and Eedi. The link is here and you can read a summary of it here by Craig Barton, Eedi’s head of education. I’ve known Craig for a long time (you can hear me on his podcast here) and have always admired his work but I have no affiliation with Eedi or Google, so this is just my view as I see it from the outside.

Here is a brief summary of the study, as I understand it.

The study took place in 5 UK secondary schools whose students were used to using the Eedi online learning platform as part of their maths lessons.

The students started an Eedi unit online in class as normal. When they got a question wrong, they were then able to start an online chat with a tutor. There were three conditions: (1) chat with a human tutor, (2) chat with an LLM tutor (whose messages were supervised by a human), (3) receive a pre-written static hint that was the same for everyone who got that question wrong.

The effectiveness of each approach was measured in three ways. (1) The students were given the exact same question they got wrong at the start. (2) If they still got it wrong, they got to have a follow up chat and then two attempts at a new question on the exact same topic. (3) The students moved on to the next unit in the sequence and the study measured their success on the first question of that sequence.

Essentially, the students got fewest questions right when taught with the “static hint” approach. There wasn’t much difference between the human tutor and the LLM tutor. The humans who supervised the LLM didn’t have to make that many edits and were themselves impressed by the LLM’s responses. Crucially, the LLM made very few errors, and the paper lists them all in an appendix.

So how does this study address my four challenges?

Questions not explanations. The student-LLM discussions were focussed on questions and answers. The LLM wasn’t just explaining a concept and assuming the student got it. It asked questions to check for understanding, and then, when the understanding wasn’t there, it was capable of recognising that and following up with other questions until the student did understand. And then of course the success of the intervention was immediately measured with the original question and a subsequent question.

Reducing hallucinations. The most striking part of this study is that the LLM error rate was reduced down to just 0.14% - just over one error every thousand messages. This is extremely impressive. It didn’t report what the human tutor error rate was, and more broadly we don’t really have reliable data on how often teachers make basic errors in class, but even highly skilled teachers will make errors from time to time. Does the average human teacher in a traditional class make one error for every thousand “messages” they speak? It’s not insane to think they might.

Improving on pre-LLM technologies. A 0.14% error rate is good for an LLM or a human, but probably not as good as a textbook or an intelligent tutoring system (ITS) which are capable of close to zero errors, especially once they get into a second edition or version. However, this study specifically compares the LLM tutor performance with pre-written static hints, which in some ways are analogous to textbooks or ITSs, and the LLM tutor outperformed the static hint. I like the concept of pre-written static hints, and I think they are under-rated, but clearly they have their flaws. They are kind of similar to the customer service chat bots that give you a pre-loaded menu of options to choose from. A lot of the time, the pre-loaded options don’t address your question, and you want to find a way to talk to a human instead.

Providing structure and discipline. The study involved students in a typical classroom. They weren’t sitting in a lab or at home. The structure and discipline of an in-person class with an in-person human teacher are present. As a result, it is much easier to see how this study - which was quite small - could scale up to larger numbers. (I still retain concerns about moving all learning on-screen, and even when screens are used I think we need to do more on optimising them for learning, blocking distractions, etc.)

There will be plenty of people who think this study isn’t ambitious enough. The things that I think are strengths – the focus on correct questions and answers, the way it is embedded in a typical classroom – they will see as weaknesses. Why isn’t it tearing down the traditional classroom and re-imagining education for the fifth industrial revolution? Those people will have to look elsewhere. For those of us in the evidence-based community, this is a significant breakthrough.

What’s also interesting is that for perhaps the first time, a major technology company are listening to the evidence about education. In my 2020 book, Teachers vs Tech, I lamented the fact that most of the big technology companies were spending their education budgets on things like “demonstrate how to solve equations with iMovie videos in the style of a cooking show”(Apple) or “different students within a single class could be completing different projects about the topic, each tailored to their learning style.” (Summit Learning, funded by Chan Zuckerberg).

If we are at a point where a major technology company is committing significant resources and talent to evidence-backed principles, then there is the potential for big breakthroughs.

The error rate is low, but it still matters

Although the low error rate is impressive and far better than I thought was possible, I still think it’s high enough to worry about. In this study, the human supervisor edited out the errors, so the results reported don’t include their impact. There are so few errors that you might argue they wouldn’t have changed the results, but at a larger scale with no human supervision, we just don’t know how these errors would propagate and affect a student’s understanding.

Also, whilst one in a thousand errors sounds low, it’s possible that one lesson’s worth of conversation with the chatbot might include 50 or so messages, which would effectively 50x the error rate. Over the course of one year of using the chatbot in every maths lesson, a student might encounter 12 errors (50 messages a lesson, 5 lessons a week, 35 weeks a year, 0.14% error rate). That feels significant enough to worry about, and significant enough that students would start to doubt the chatbot even when it was right. Obviously what would be great is if we could have a chatbot with zero errors, but I think we are in real “March of the Nines” territory here - it is often as difficult to get from 99% accuracy to 99.9% as it is to get from 0% to 90%.

Instead, I think we need to focus more on the social norms around errors. If a human teacher makes a mistake, they often know about it because two or three students look puzzled and raise their hands and say “Miss, you’ve made a mistake”. (This is one of the advantages of a large and non-personalised classroom - the teacher gets feedback from multiple sources). What should a student do if they think a chatbot has made a mistake? What process should we put in place to deal with those errors?

This is an issue for all uses of AI. In many cases it already makes fewer errors than humans, but it makes different kinds of errors in different ways. We have established and often centuries-old systems for catching and mitigating human errors. A lot of these just don’t work with AI, so we need to build new error-mitigation systems.

What are the implications for other subjects?

This paper solely looks at maths. What about those of us involved with teaching and assessing other subjects? At No More Marking, we focus on writing, and for the last couple of years we have been looking at ways of getting LLMs to provide useful feedback on student writing. You can read a summary of our journey here.

What we would really like to do is provide students with specific questions on specific aspects of their work that they can answer and that will improve their work. Last year, we ran a project called CJ Dynamo which tested the effectiveness of the various types of feedback we are able to produce.

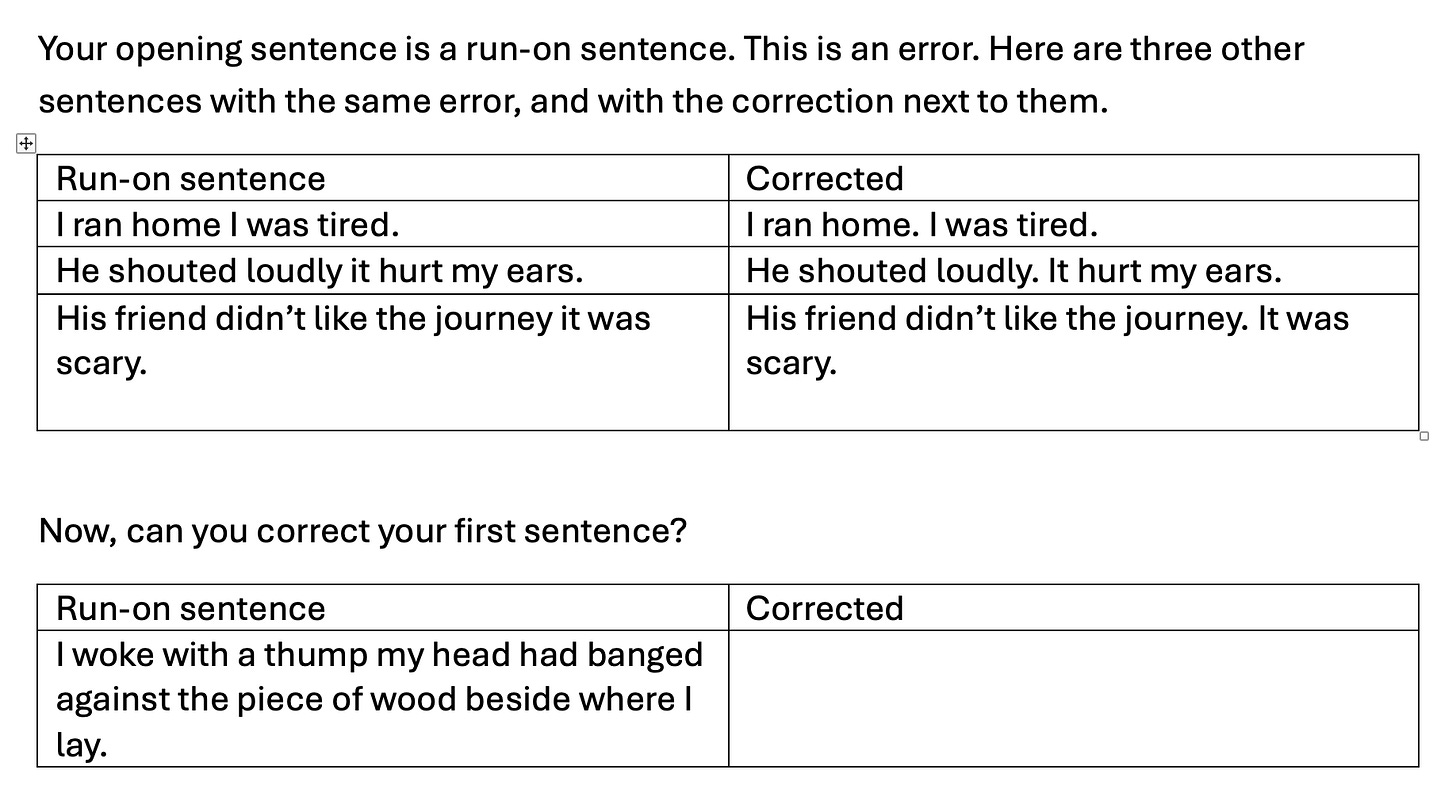

We’d like to improve our feedback further. Here’s a fairly simple example of what we’d like to do.

Here’s an extract from a piece of work by a student.

What we’d like is for the AI to automatically produce something like the following.

We are not able to get LLMs to do this reliably enough. Instead, we’ve settled on a different approach.

The AI produces some personalised but less specific advice about the content of the writing, where it is less likely to go wrong.

We create sets of multiple-choice questions about the technical aspects of writing, which we allocate to students based on scaled score – not on whether they have made that specific error or not.

We also have personalised AI-transcribed teacher feedback based on audio teacher comments

Our current multiple-choice questions are more like the “static hint” approach in the Google paper. This is better than nothing, and our CJ Dynamo project shows it is having a positive impact. However, it would be better to have something more personalised and dynamic, and the way to do so is probably by fine-tuning an open-source LLM. This is possible and we are working on it – but it is hard and expensive, which is probably why Google are leading the way in this area currently!

I had read of this RCT in your previous post and I was intrigued. There are a few remarks which came to my mind: in general terms, I think that what Google tested wasn't a model for AI tutoring, but for human, AI-assisted tutoring.

1) While the error rate was very low, 23.6% of the answers of the LLM were changed by the tutors before being submitted to students. Those answers weren't wrong altogether, but the tutor intervened to tweak them somehow. Basically, responses from the AI-tutors benefited from a revision the human tutors didn't receive. The same happened when human tutors where assisted by Tutor Co-PIlot, only with the roles reversed. I think Google should have taken this into account, when calculating the effectiveness of the AI-tutors compared to the human ones.

2) Since every response from AI tutors was revised by human tutors, the typical LLM drift effect was eliminated. Errors and subpar answers can't stack up thanks to the oversight, while an unsupervised AI tutor might eventually go off track. On the other hand, if the sessions with AI tutors are brief enough not prevent bugs to accumulate, the problem might be less significant or it may resolve itself whenever the AI is rebooted.

I'm happy to see that the classroom setting remains central to learning. The social side of learning is still important, as noted by you when talking about the mistakes human teachers occasionally make in class.

Furthermore, recent research seems to show that making mistakes can be so beneficial that one should consider making them deliberately. Without going that far, being in class and seeing someone else make a mistake can be quite useful (as can, more broadly, hearing the different perspectives of other students.

I read your November 2025 post, so seeing such a quick turnaround on the possibilities of LLMs as tutors is amazing. It seems Google is approaching this from multiple directions; it's also raising the bar on textbooks through Learn Your Way, which personalizes them instantly for every student using principles from the science of learning like dual coding. (There are real risks with that approach too, of course.)

Now, what you were attempting by generating a personalized report that diagnoses and exemplifies the problem before showing it in the student's own text is a great approach. LLMs are pretty bad at plain-old proofreading. Apparently, it has to do with the fact that the training data used by LLMs includes far more polished, publication-ready text than drafts-in-progress, so the model never really learns what "in between" looks like. No More Marking can probably train it by showing large volumes of drafts and final versions, which is what you may be doing already.

That said, LLMs are strong at rewriting drafts into polished versions that are generally error-free. If I had a sufficiently large budget, I'd probably exploit that for training: ask an LLM (specifically, Claude) to rewrite a student text respectfully, then have a second LLM compare the draft and the rewrite, identify what changed, and use that comparison to show the specific corrections that were needed. It's a roundabout route to the goal, but it plays to LLMs' actual strengths.