You can't assess your way out of a curriculum problem

But you can do some research

All the goals we are interested in in education are long-term. When you teach English, you want your students to be able to write clear emails and love beautiful poetry years after your lessons. When you teach maths, you want your students to be able to calculate the impact of compound interest on their mortgage and to find patterns in numbers long after they leave school. Whatever subject you can think of, it's unlikely that any teacher would be happy if their student aced the end of school exam and then promptly forgot everything they had learnt.

This might sound like the start of an anti-assessment screed, but in fact classic assessment theory would largely agree with what the paragraph above. It doesn't matter what score a student gets on an exam. What matters is what that exam score allows you to infer about what a student knows and can do, and most of the inferences we want to make are not that short-term. For example, employers and universities will often look at exam scores that are already a couple of years old, but they still expect that they can learn something useful from them.

Plenty of assessment structures and revision strategies compromise long-term inferences. Perhaps the most obvious example is cramming: it is possible to get a high score on a test which reflects your short-term mastery of the material, but which does not correspond to your long-term understanding.

What kinds of assessment design promote cramming? People often think that terminal exams are the culprit here. If all the exams are at the very end of a two-year course, say, then some students will not bother studying for the bulk of those two years, and instead cram everything into the final month or so. If they work hard in that final month and have good short-term memory then they can come out with high grades that do not reflect their true long-term understanding. Of course this is a real problem, and one that many teachers will have seen in practice.

But that is not to say that any alternative assessment structure is guaranteed to be better. It's often suggested that coursework and modular assessments will lead to less cramming than terminal exams. But the problem with this is that modules and coursework are even more prone to short-term cramming, because each assessment covers less content, making it easier to predict what will be assessed and to cram for it. When national exam systems have been based on modules, this is what has happened. After the introduction of A-level modules in 2000, one review noted that individual modules came to be seen almost as separate subjects, whilst another said that modules had led to ‘compartmentalised learning’ and made it harder for students to ‘connect discrete areas of knowledge.’ When such systems are used for school’s internal assessment systems, Dylan Wiliam has noted the following:

This results in what I call a ‘banking’ model of assessment in which once a student has earned a grade for an assignment, they get to keep that grade even if they subsequently forget everything they knew about this topic. It thus encourages a shallow approach to learning, and teaching. Students know that they only have to remember the material for two or three weeks until they take the test on that material, and they can then forget it, so there is no incentive for the student to gain the deep understanding that is needed for long-term recall.

So what is the solution? Is there a way to eliminate cramming completely? Here are my suggestions.

First, we should stick with terminal exams. They are not perfect and they certainly do make cramming possible, but they do also leave a space for schools and students to design curriculums and revision structures that promote long-term learning. By contrast, modules and coursework actively encourage a cram-and-forget approach.

Second, we have to acknowledge that this is not just an assessment issue - hence the title of this post: you can’t assess your way out of a curriculum problem. I am all for improving assessments to make them us ungameable and as effective as possible, but I think the best we can do is to create assessments that open up space to teach effectively. I don’t think we can invent assessments that guarantee effective teaching or that can't be misused, particularly given that many students have big misconceptions about what how long-term learning happens. Instead I think what we have to try and do is to surround assessments with supporting curriculums and resources which promote long-term learning, and to communicate the principles of effective learning and revision clearly to students - perhaps with online courses like Barbara Oakley’s Learning How to Learn.

Third, we should do more long-term validation of assessments. For obvious reasons, we do have to assess students at their end of certain phases of education. But we can still follow up with research on how they are getting on in later years, to see if their exam results did predict longer-term learning. What we'd be trying to assess here is in a sense not the performance of the student - but the performance of the particular assessment or curriculum & assessment package. A great recent example of this is from the researcher Stuart Cadwallader at Ofqual, who followed up A-level science students in their undergraduate university labs to see if the new A-level science coursework had affected their practical lab skills.

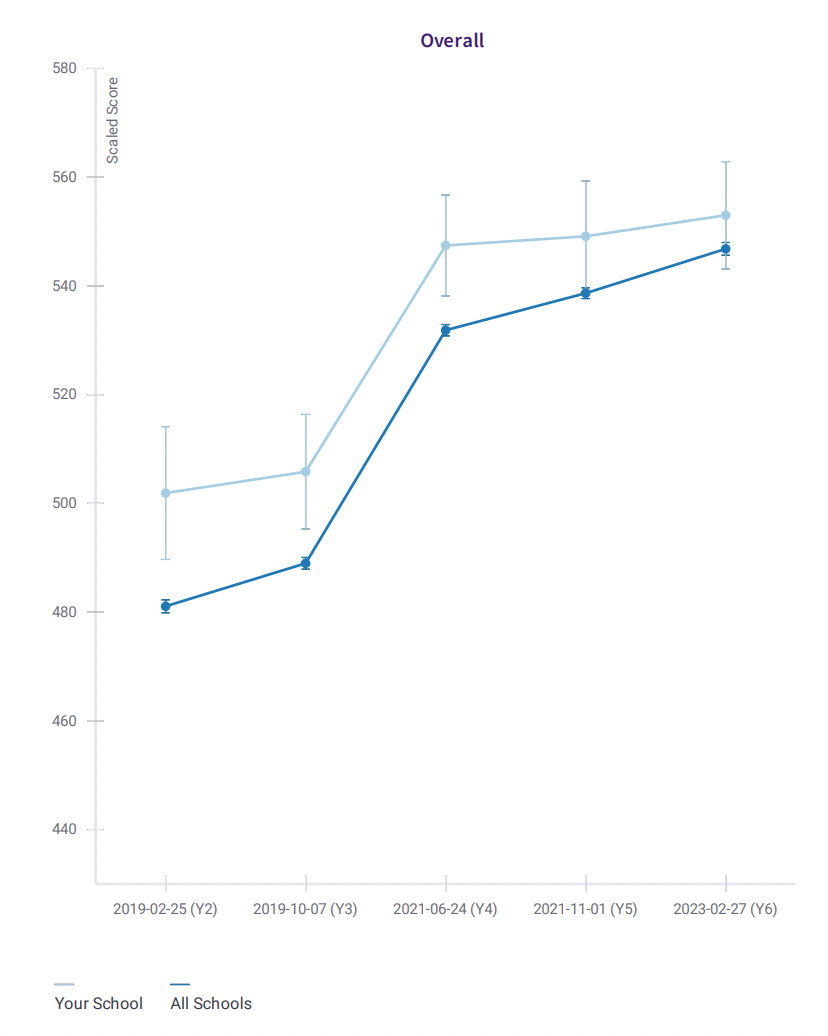

Fourth, we should do more multi-year education research. If we all agree - as I think we do - that learning is long-term project, then why does so much research measure the impact of interventions that are a year or even just a few months long? Doesn’t that just further encourage short-term tactics that don’t lead to long-term learning? I’m inspired here by the recent Colorado study of a multi-year content-rich reading curriculum, which found the curriculum produced big gains over time. And at No More Marking, we have been working with many schools for five years, and are able to present them with multi-year data on their students’ progress, as you can see below.

So you can’t assess your way out of a curriculum problem - but there are a lot of things you can do to make cramming less likely.

I don't know enough about 3rd level. I know that at A-level Eng Lit Ofqual have had concerns about a race to the bottom, with schools choosing short and relatively easy texts. See p 15 here. I think in the end The Yellow Wallpaper now can't be studied as a standalone text because of concerns about this.

Excellent piece. The notion that terminal exams should be scrapped in favour of assessment by teachers responsible for teaching, as suggested when exams were suspended during COVID, sound have been disastrous. One need only look T the rampant grade inflation for GCSEs and A Levels. The latter creating serious issues on university selection processes. Terminal exams, followed up by assessment at a later point eminently sensible imho.