How to write a good rubric (for humans and AI)

Don't be like José Mourinho

Last term, we ran a national history assessment on the topic of the Battle of Hastings. The essays were judged by a mix of human and AI judges, and we saw pretty good levels of agreement between the humans and AI, and barely any glaring AI errors.

Still, that does not stop our teachers - and us - asking a set of questions about how the AI makes its decisions. What does it value? Does it value historical accuracy? Does it notice when claims are false? Does it base its judgements on fluency of writing or quality of historical analysis? What weight does it give to the various aspects of a good essay? And - a question we are getting more and more - what kind of rubric or guidance should we give the AI to help it make the best decisions?

To explore this, we ran a small experiment.

We selected a sample of the c. 4,000 essays and got an AI to isolate every truth claim in every essay and then to assess whether each claim was true or not.

This is not as simple as it sounds, and an essay about the Battle of Hastings is probably not the best test case for this approach, because there is a lot about it that is genuinely uncertain: did Harold really die after being hit in the eye by an arrow? Exactly how long did it take Harold and his men to march from Stamford Bridge to Hastings?

Still, there are plenty of known facts about the Battle, and generally speaking the AI was good at spotting these and assigning a truth score for each essay. We reviewed these “truth scores” and felt they were broadly correct.

Next, we looked at whether these truth scores correlated with the scaled score given to each essay. We expected a weak positive correlation. What we actually found was a negative correlation.

In other words, essays that contained more false statements were, on average, getting better scores!

What on earth is going on?!

This is not about AI

We don’t think this problem is an AI problem. We’ve seen something similar in the past with writing rubrics long before we used AI in our assessments. (In fact, I wrote an article about a similar issue with writing assessments almost ten years ago, before I started working at No More Marking, and before chatbots existed!)

Essentially, when you give pupils an extended writing task, the more they write and the more ambitious they are, the more chances there are for them to make errors. The very best and most creative responses can therefore have more errors than weaker responses.

Here is a great example from the history assessment.

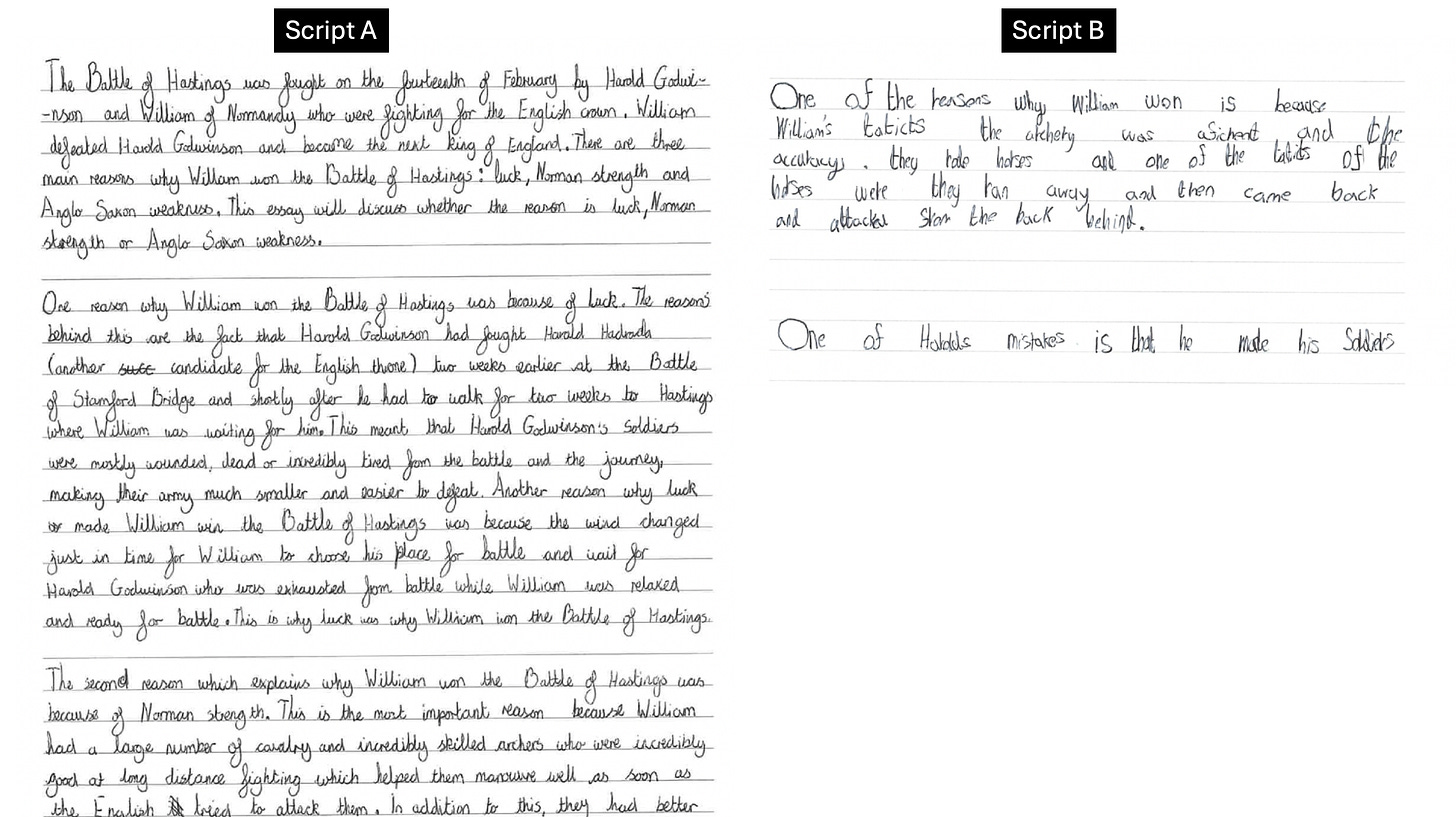

Script A is the first part of one of the highest-scoring essays. Script B is the entirety of one of the lowest-scoring essays.

Script A has a straightforward factual error in its first sentence: the Battle of Hastings was not fought on the 14th February 1066 but the 14th October. The second paragraph also has some factual issues: it says “Harold Godwinson’s army was mostly dead, wounded or incredibly tired from the battle and the journey, making their army much smaller and easier to defeat”. This is all a bit more arguable, but “mostly” is probably too strong here, and “much smaller” depends on what your reference point is: it was probably smaller than it would have been if there had been no Battle of Stamford Bridge, but it also probably wasn’t much smaller than William’s army. These were all flagged up by our AI truth checker.

Script B has no factual errors at all. Our AI truth checker judged it all to be correct, apart from the final unfinished sentence which was “unverifiable”.

However, when the scripts were assessed as part of our national history project, both the teachers and the AI thought that Script A was better than Script B. I agree and I cannot believe that any history teacher would seriously argue that B is better than A.

Cardinal Richelieu and Jose Mourinho

There’s a famous line alleged to have been said by Cardinal Richelieu: “Give me six lines written by the hand of the most honest of men, and I will find something in them to hang him.”

Is that the message we want to send to our children?

The football manager José Mourinho has a touch of the Cardinal Richelieus about him. According to a biographer, in his later managerial career he developed an uncompromisingly cynical approach to football tactics, which included the following principles.

Whoever has the ball is more likely to make a mistake.

Whoever renounces possession reduces the possibility of making a mistake.

Whoever has the ball has fear.

Whoever does not have it is thereby stronger.

Interestingly, in Mourinho’s case, this strategy was not hugely successful. His biggest successes came before he developed this approach, because in football, success is not measured by who makes the fewest mistakes, but by who scores the most goals.

If you push these strategies to their ultimate limit they become entirely self-defeating. You end up with football teams trying not to play football and writing lessons that are about avoiding writing. Ultimately, if you want to win football games you have to try and play some football. If you want to be a good writer you have to write something. Neither writing nor football are exercises in trying not to make mistakes.

So does this mean factual accuracy doesn’t matter?

I think people are really surprised when I make this argument, because I have basically made a career out of saying factual accuracy is important.

And I haven’t changed my mind. I still think factual accuracy is supremely important, I still think that historical understanding is built on accuracy, and I still think we should teach students facts and get them to memorise them.

My objection is not to teaching & assessing facts. My objection is to using essays to assess facts. That’s for two reasons.

Essays are not designed to test factual accuracy

An essay is an open-ended task, which means that students have some freedom in how they respond to it. This means that students will essentially set themselves different tasks. Some students will choose to mention the date of the Battle of Hastings, and some won’t. If you have a very strict rubric that insists on factual accuracy, then the student who chooses to mention the date and gets it wrong is penalised. The student who chooses not to mention it is not penalised, even though they may not know the date either!

So the essay is basically a terrible way of telling if a student knows when the Battle of Hastings happened. The right way to assess this is with a simple short answer or multiple-choice question, where every student is given the same question and there is one clear right answer.

Short answer questions and multiple choice questions are often seen as being too simplistic or basic, but they are really powerful tools. Essays and MCQs are complementary - like the two wing mirrors on a car. They give you different views of the same reality. Don’t make your essay responsible for incentivising and measuring factual recall. Set an accompanying quiz, and let that do the job instead. (We have a nice system that will do this for you!)

If you do that, I think then you would see a strong correlation between scores on the quiz and scores on the essay. In fact, when we have tried this with writing, we do see strong correlations between simple quizzes on spelling & grammatical features, and overall writing quality.

I can’t prove it, but I suspect if we gave student A and B ten questions on the facts about Hastings, student A would do better than student B.

If you use essays to assess factual accuracy by creating a strict rubric, you will create terrible incentives

One of the things we saw - and still see - with very prescriptive writing rubrics is that you get awful second-order effects. Your rubric does not end up incentivising factual accuracy. It incentivises short and basic pieces of writing. Once teachers and students know that factual and grammatical errors will be penalised heavily, they take the Richelieu / Mourinho approach and become very negative and defensive.

What does this mean for rubric design?

Whether you are using human or AI markers, you have to allow your markers some discretion.

Open-ended tasks give pupils discretion. If pupils have discretion, then markers must have discretion too. Otherwise, you create distortions.

So a principle for both humans or machines is as follows: Do not use prescriptive criteria to judge extended writing.

We’ve found that humans can judge accurately and consistently using just one incredibly holistic criterion: which is the better response?

We think the AI does need a bit more guidance than this, but it should still have latitude to make holistic judgements. We have a section on our website where you can paste in your criteria, and some advice on setting holistic criteria here. We will update this with more examples and advice as we trial assessments in different subjects.

You can trial different criteria and assessments yourself. You can purchase AI custom task credits on our website, and we are also giving away 30 free AI credits to everyone who attends our next introductory webinar on 25 February.

If you are already using custom tasks, let us know in the comments what criteria you’ve used.

Thanks for this. Very interesting as always. How effective can essays be in testing factual knowledge if they are positively marked for knowledge? So, essay A doesn’t need to be penalised for the errors but can be rewarded for, eg, knowing that William was from Normandy and that he defeated Harold Godwinson.

To extend your football metaphor. We don’t have to penalise the shots off target, we can just ignore them and count the ones that hit the target. This rewards more the pupils who take the most shots, and rewards even more those who score the most goals.

That feels like the approach we currently take in Geography (GCSE and A Level) already anyway.

As a teacher of A level chemistry Iwelcomed, with open arms, the Shift to "Highly Structured" Questions.

Before 1990, Chemistry A-levels often included "Section C" or "Paper 3" style questions that required continuous prose.

This was done to increase "construct validity", ensuring students were being tested on their chemistry knowledge rather than their ability to write a structured English essay.

By 1995, most questions had been broken down into sub-parts (a, b, c, d) that guided the student through the logic.

The downside was that students became less able to link ideas and think critically.

I assumed the death of the "chemistry essay" was the availability of skilled exam markers.