What is Comparative Judgement and why does it work?

Humans and AI prefer comparative judgements to absolute ones

At No More Marking we run online Comparative Judgement assessments of extended writing. We've been doing this for 10 years and for most of that time we've solely used human Comparative Judgement. In the last year or so, we've experimented with using AI judgements. In this post, we're going to give you a summary of what Comparative Judgement is and what it means to add artificial intelligence into the mix.

So what is Comparative Judgement?

Comparative Judgement is a different way of assessing extended writing.

The traditional way of assessing writing to use absolute judgement, where you look at one piece of writing and you look at a rubric and decide which category of the rubric best fits the piece of writing.

With Comparative Judgement, you look at two pieces of writing and make a holistic decision about which one you think is better.

You and lots of other judges make a series of decisions like this, and the Comparative Judgement algorithm combines them all into a measurement scale for every piece of writing. It’s quicker, more reliable and more valid than making absolute judgements with a rubric.

The reason why it works so well is that it goes with the grain of the way the human mind works. We are not very good at making absolute judgements, whatever it is we are judging - height, colour, pitch, temperature, etc.

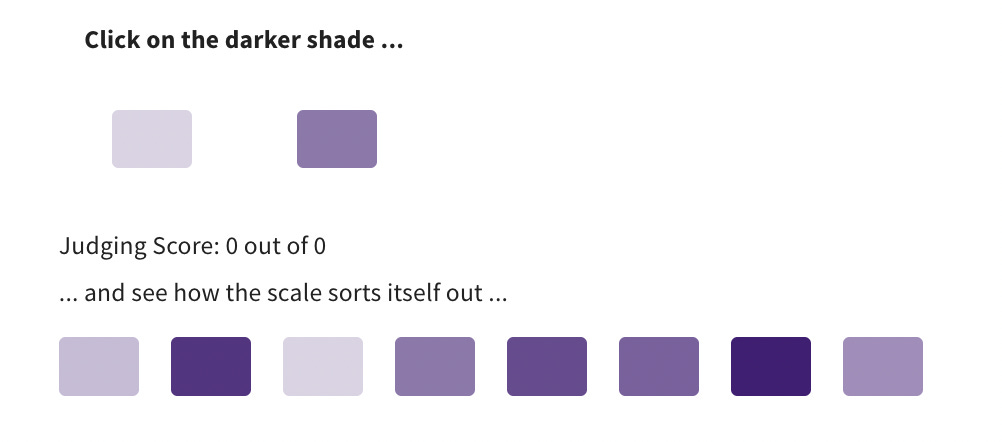

We have built a simple interactive demo on our website called the Colours Game which demonstrates this point. You are asked to do some absolute judgement of eight shades of the colour purple, and then some Comparative Judgement. Most people get under 50% right on the absolute judgement task, and 100% right on the Comparative Judgement.

Absolute judgement against a rubric feels very objective, but the data shows it is quite subjective. Different markers can all be using the same rubric, but they will still disagree about the mark a piece of writing deserves. In fact, it is worse than that: markers don’t even agree with themselves. If you ask them to mark a piece of writing one day and then come back a few weeks later and ask them again, they will often change their mind!

Comparative Judgement is the opposite. It feels very subjective - but the data shows it is actually far more reliable.

Human Comparative Judgement - the gold standard of human judgement

Comparative Judgement is a well-established principle. It is not a new idea and it is not something we invented. The theory and algorithm were developed in the 1920s by an American psychometrician called Louis Thurstone.

We have used it to assess nearly 3 million pieces of writing since 2017. We link all our assessments, which means that you can compare scores on our writing scale across time. You can read one of our early peer-reviewed pieces of research here, and a study here from 2020 which compared the grades awarded to 349 pieces of writing using Comparative Judgement and a traditional rubric-based approach.

Other independent research confirms its effectiveness. For example, this paper by Ofqual showed that Comparative Judgement delivers the same accuracy as traditional double marking in half the time. Exam boards use Comparative Judgement to help set grades and maintain standards.

And it is not just education. Comparative Judgement is used in many other fields. Chatbots will sometimes get you to do Comparative Judgement - they’ll give you two responses to a question and ask you which you prefer. They will use your answer - and millions of others - to improve their responses in the future.

What happens when we ask AI to do Comparative Judgement?

When we started out trying to get Large Language Models to assess writing, we began by asking them to do absolute judgement. That is, we gave them a piece of writing and a rubric and asked them to mark the piece of writing. Plenty of other organisations have tried something similar.

We’ve found the results of all these trials to be underwhelming. Yes, it’s true that on some metrics the LLM will be as good or even better than human markers - but that’s a bit misleading, as humans are pretty poor at absolute judgement! We also found that even when the overall metrics were good, LLMs would make big and inexplicable errors.

So we switched tactics, and asked the LLMs to make Comparative Judgements too.

We have found that, like humans, LLMs are much better at Comparative Judgement than absolute judgement! We’ve also found high levels of agreement with human judges - LLMs agree with humans about 80% of the time. Human-human agreement is about 85%.

Crucially, most of the human-LLM disagreements are quite small. Even more crucially, so far, all of the big disagreements have been the result of human error - not LLM error. Most of those errors have been the result of handwriting bias from the humans.

Our new AI-enhanced judging model

We have now integrated AI judges into our assessments, and allowed schools to choose what proportion of judgements they want to be completed by AI. We recommend completing 90% of the judgements using AI, which will reduce the time taken to judge by 90%, but retain a human link. The human judgements will validate the AI judgements and ensure that each piece of writing is seen twice by a human. The AI can provide feedback too.

We run frequent training webinars where participants can try out judging and see if they agree with the AI.

We’ll keep this Substack updated with what we learn this year.

You're raising a super important point for teachers to consider in their use of AI.

But since I've spent no time in my life associating the number 4 with a particular shade of purple, the color game isn't a good analogy for marking with absolute standards.

And since I've spent many years reading and writing, I have strong programmed criteria and intuitions about someone's writing ability without requiring comparisons on the same task.

For example, when I first read a substack essay years ago, I didn't sit there in confusion until someone showed me another post on the same topic as a comparison point.

Comparison grading works better under high-constraints testing where the entire point is to differentiate students, even if they all perform really well (or really poorly).

For many other situations, inside and outside of education, absolute criteria are critically important for evaluation.

Fascinating. I’ve just started experimenting with LLM referenced marking and am finding it very useful. Will refer my head teacher to your material.

On a different note, I would like to suggest that many of the issues identified with absolute marking stem from some very shoddy, widely used rubrics. In the IB and Australian systems, the criteria descriptors for marking essays are written in vague, borderline esoteric language that is barely comprehensible to most teachers, let alone students. When I’m feeling snarky, I think that this is so the respective systems can avoid accountability. If teachers and schools took/had the time to craft clear, task-specific criteria, it would go a long way to building confidence in the process of assessment. Even better, students would have comprehensible guidance about what they need to do and how they can improve.

Thank you.